On the Road with the Water Protectors of the Rolling Resistance

by Mikka Macdonald | March 29, 2018 12:03 pm

Mni Wiconi is a battle cry: Water is Life.

And members of the Rolling Resistance are fighting for their lives on a daily basis.

They are fighting for the life of indigenous cultures that are are ignored or exploited. They are fighting for the life of indigenous ancestral lands, that oil companies tear through for personal profit. And they are fighting for the life of indigenous people that the United States have long viewed as collateral damage our quest to build a more perfect union.

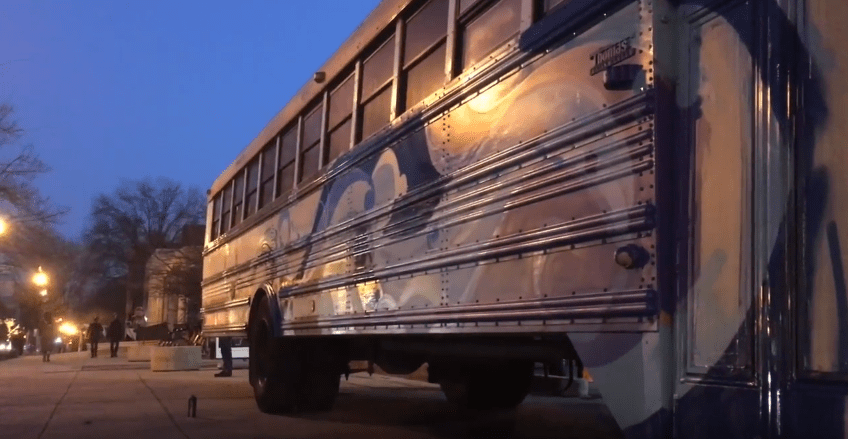

When the Rolling Resistance’s repurposed school bus — stretching forty-five feet long, displaying light blue plates that read “Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians,” and carrying fifteen water protectors — came to Washington, D.C. in early March, it was a homecoming.

After the raids at Standing Rock in North Dakota last year, the District of Columbia became a hub where many of the water protectors reunited: The capital was a place where communities of indigenous warriors came to heal, mourn, and draw a roadmap for what they were going to do next.

One year later, the Rolling Resistance came back, continuing the fight.

I spoke to some of the water protectors as they prepared for an art and music open house in Cleveland Park. Inside an expansive warehouse-style building, members of the Fourth Generation Kitchen cooked dinner, musical performers began to set up the sound system, and vendors and artists hung their art along the walls.

Outside, the repurposed school bus was parked on the sidewalk. A large reminder of the mobility of the resistance.

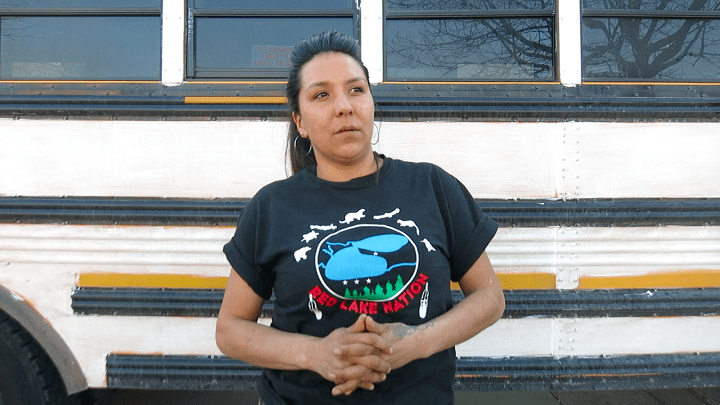

Hennessy.

While many of the water protectors have taken breaks from their frontline activism over the past year, Hennessy is one of the activists who have remained at the forefront of the fight: she has continued a life of living at camps, at protests — and often, out of the bus.

Even though the temperature was dipping below zero as we spoke, Hennessey stood comfortably and unfazed in a black t-shirt, with the words “Red Lake Nation” printed on it. Her hair was pulled back, and she held herself with the confidence of a protector who knew that she would never back down.

Coming back to Washington, D.C., “is us continuing our journey that we started last year,” said Hennessey. “The bus … brought a lot of us warriors back to where we needed to go.”

Now, she is with the majority of the other members of the Rolling Resistance at Line 3, in her home state of Minnesota.

Line 3 is the proposed project by Enbridge, a Canadian energy transportation company, that would parallel an eroding pipeline that runs from Saskatchewan, Canada, through Minnesota, and into Wisconsin. It is called the “Line 3 Replacement Program” — but instead of replacing the old pipe it only doubles the size of Enbridge’s presence in the region by ordering the construction of a new line.

It tears through indigenous people’s wild rice field, and threatens environmental destruction along its nearly 1,000-mile length. As Hennessey protests Enbridge’s attempts to build another pipeline, she worries that the camp will turn into another Standing Rock.

“It’s not uncommon to see semis or pipelines coming in… and caravans of workers,” she said.

“I see similarities to last year [at Standing Rock],” said Hennessey. “Stuff happening with the police, escalations amongst the people who are trying to protect [the pipeline].”

After the terror and violence that the water protectors faced at Standing Rock, there is clear worry and heartbreak at the sight of oil companies continuing their assault on other land.

Brandy.

Brandy is fierce, smiling, with long dark hear that whips around her in the wind as she talks.

She is from Saskatchewan, Canada, in her thirties, and has been protesting with the Rolling Resistance across the United States, including Standing Rock and — most recently — Line 3 in Minnesota.

Line 3 runs directly from her home, and the fight against the pipeline is personal. “My parents don’t have clean drinking water,” said Brandy. “And that’s my whole life. It’s something that I can’t just look away [from] just because Standing Rock is over.”

Like many of the water resistors, she has learned how to reconcile her life on the front lines of pipeline protests with her role as a parent and a daughter.

“I could just … go home, and be a mom, and be safe,” she said. “You know, I do own a business. I do have a job. So I really try to balance everything. So I mean, I could throw in the towel, but that’s ridiculous at this point because my daughter is also an indigenous activist.”

Her fifteen-year-old daughter has joined the fight as a water protector. She has joined her mother at Standing Rock, and on the Line 3 fight. And she looks up to her mother and what the Rolling Resistance is doing.

One of the challenges, according to Brandy, is to ensure that her daughter is safe and educated. She needs to be “well-informed, being an indigenous activist already at such a young age.”

This activism is necessary for change, but it comes with risks.

Brandy’s actions has led to her name appearing on government watch lists. She regularly receives harassment because of her vocal, political voice — in one instance, the breaklines on her car were cut in an act of violent suppression.

As she talks, she describe two worlds and roles that she has to balance on a daily basis.

“Day-to-day right now, I am re-establishing myself,” said Brandy. “You have to take it, and get on with your day, and hope that no one seriously injures you.”

Still, the challenges and the adversity are worth the fight.

“We have a duty to protect the water,” said Brandy. “To protect the earth. We belong to the land, not the other way around.”

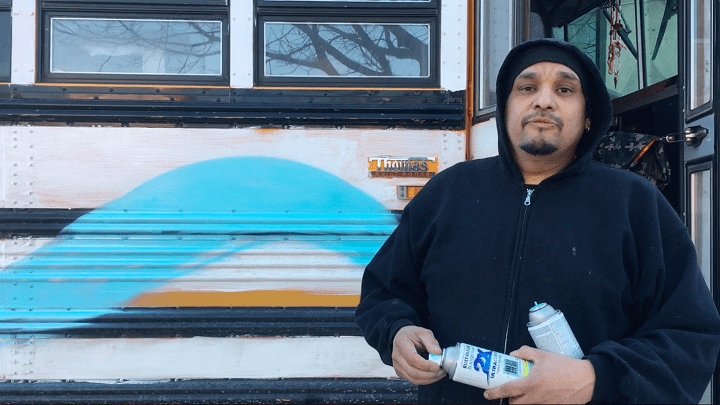

Traz.

Traz is from Chicago, Illinois, and — like most members of the Rolling Resistance — came to Washington, D.C. from Line 3. When I spoke with him in early March, he was beginning to paint the side of the school bus.

Like the drums, music, and dancing, visual art is part to the Rolling Resistance activism. It is an integral part of the resistance, and it is an integral part of the healing.

Traz holds a spraypaint can with one hand, and gestures towards the bus with the other. “We’re water protectors, so this is going to have a water theme to it. This is part of the medicine of what we’re doing,” he said. “[And] we’re honoring black bear. So that’s going to be part of this well. ”

He walks, smiles, and looks at the bus with a mix of familiarity and appreciation.

“This is going to be a flow of waves and water forms,” said Traz, pointing to the bus. “And whatever else the universe decides, we’ll throw in there. We’ll see what happens.”

At the end of the night, the bus is painted with vibrant blue waves rushing down it’s side. On the front is giant bear and bear claw. On the back are the words, “Water is Life.”

It is quiet end to an emotional night.

“Standing Rock and this whole movement started over 500 years ago,” said Traz, his voice lowering slightly. “This is one of the bigger battles. And we’re not done.”

This article is the second in a two-part article series about Indigenous Rights. Read more from the Center for Community Change by visiting Change Wire.

Learn more about the Rolling Resistance here.